Beyond Lagos: How Independent Nigerian Cinema is Building Sustainable Creative Economies

Author: Taiwo Egunjobi

In 2019, I shot my debut feature film In Ibadan with a crew of twelve people and a budget that would barely cover catering on a mainstream Nollywood production. We filmed in the city where I grew up, telling a story about young Nigerians navigating love, economic uncertainty and their relationship with the ancient city. Five years later, I've made three feature films, founded a production company, ran a film festival, and witnessed an entire ecosystem of independent Nigerian cinema emerge from the margins into something that feels increasingly like a movement.

Credit: via Google

This is not the Nollywood most people know, not the Lagos-centric, high-budget theatrical releases that dominate headlines. This is something quieter, scrappier, and perhaps more sustainable: a new generation of filmmakers building creatively outside traditional industry structures, leveraging technology and global distribution platforms to tell stories that move them. And in doing so, we're not just making films. We're building an economic model for creative work in Nigeria that could outlast any single box office trend.

The Real Economic Story: Micro-Economies and Sustainable Work

When industry analysts discuss Nollywood's economic contribution, often citing figures around 2.3% of Nigeria's GDP; they're usually talking about the commercial theatrical sector concentrated in Lagos. What goes uncounted are the dozens of smaller production companies across Nigeria creating steady employment through lower-budget but more frequent productions.

Credit: Wikipedia

My production company, Sable Productions, operates on this model. Each of my four features, In Ibadan (2019), All Na Vibes (2021), A Green Fever (2024), and The Fire and the Moth (2025), has employed between 30-50 people across pre-production, production, and post-production phases. These aren't just actors. They're location managers, sound recordists, production designers, makeup artists, drivers, security personnel, and catering staff. For a three-week shoot in Ibadan, we inject money directly into the local economy: hotel bookings, restaurant bills, equipment rentals, location fees paid to homeowners and institutions.

But the more interesting economic story is what happens after the shoot. Unlike the old Nollywood model where films were rushed to market and quickly forgotten, digital distribution creates longer revenue tails. A Green Fever premiered at AFRIFF in November 2023, then became available on Amazon Prime Video in February 2024. By 2025, it is still generating income and has now started its ancillary release to airlines. This matters because it means filmmakers can plan their next project rather than scrambling immediately for any available work.

This is decent work in the truest sense: creative labor that pays fairly, sustains livelihoods, and builds toward something cumulative rather than extractive. When I hire crew members, I prioritize proper contracts, reasonable working hours, and payment schedules that respect people's dignity. This isn't altruism; it's pragmatism. A crew that trusts you, in return for the next project. The challenge, of course, is that this model requires patience that Nigerian economic realities don't always permit. My cinematographer might work on my film, then immediately take a commercial job to pay bills. Our production designer freelances across multiple projects simultaneously. The industry hasn't yet created structures: proper unions, standardized rates, health insurance, pension schemes that would make creative work truly stable.

Credit:Taiwo Egunjobi

Digital Technology as Equalizer

I studied Psychology at the University of Ibadan, not film. I learned filmmaking by doing it; shooting short films as an undergraduate with borrowed cameras, teaching myself editing software through YouTube tutorials, studying cinematography by watching films frame-by-frame. This would have been extremely difficult to do 20 years ago. The democratization of filmmaking technology is the single most important infrastructure development in New Nollywood.

Today, you can shoot a feature film on a camera that costs less than what a single film reel cost in the analog era. My early films were shot on relatively affordable digital cinema cameras that generally produced images comparable to international productions. Post-production happens on laptops. Color grading, sound design, visual effects; all the technical crafts that once required expensive facilities are now accessible to anyone with decent equipment and Wi-Fi.

But here's where the infrastructure story gets complicated. Nigeria's electricity supply is better these days but remains catastrophically unreliable. During the edit of A Green Fever, we calculated that generator fuel costs added approximately 15% to our post-production budget. Internet bandwidth, while improving, still makes uploading large video files an overnight affair. We still don't have enough film schools to produce highly skilled crew members. Infrastructural deficits affect filmmakers negatively across the production cycle.

So we manage. We buy kegs of petrol, we buy multiple internet services, we build relationships with the few reliable equipment rental houses and hope for the best. We share resources across productions. As inaugural festival director of The Annual Film Mischief Festival, part of the motivation was creating infrastructure ourselves, a platform for screening work, building audience, fostering critical discourse, because we couldn't wait for institutions to provide it.

The arrival of international streaming platforms - Netflix, Amazon Prime, Showmax - has been transformative, though not in the way many expected. Yes, they provide distribution and revenue. But more importantly, they've validated a quality threshold. They've proven that Nigerian films can meet international technical standards and begin to find global audiences. A Green Fever and The Fire and The Moth streams in multiple countries. People in the diaspora discover it. This creates pressure to maintain quality and opens doors for co-production conversations.

Regarding AI and emerging technologies, I'm cautiously optimistic. AI tools for script coverage, scheduling, and even some post-production tasks, could reduce costs and increase efficiency, but only for skilled practitioners who understand the craft deeply enough to guide the technology. But cinema is fundamentally about human perspective: the specific way a Nigerian filmmaker sees the world cannot truly be automated. We need to be deliberate about how we adopt these tools.

Credit: Wikipedia

Stories as Infrastructure: The Responsibility of Independent Cinema

I make thrillers and noir films not because they're commercially safe but because genre provides structure for exploring social questions. All Na Vibes used the framework of neo-realism to examine how young Nigerians navigate economic dysfunction and institutional failure. The Fire and the Moth employs thriller mechanics to investigate guilt, consequence, and the weight of local mythology.

This is where independent Nigerian cinema intersects with every SDG goal imaginable. My own films are striking examples: young people trying to work and survive (In Ibadan and All Na Vibes ); the legacy of culture (The Fire and The Moth ).

Documentary filmmakers working in Nigeria experience development challenges even more directly.Some of my work is also in documentary. I have told stories about subjects as diverse as Ibadan business communities, natural African black hair, and Christian persecution in Northern Nigerian Communities. These films create awareness, yes, but they also serve as evidence, as advocacy tools, as historical records.

The challenge is sustainable funding for this work. Grant organizations come and go. Government support is minimal. Commercial viability for serious independent work remains uncertain. Many filmmakers subsidize meaningful projects with commercial work - a necessary compromise, but one that slows the pace of important storytelling.

Credit: Taiwo Egunjobi

Looking Forward: What Sustainable Nigerian Cinema Requires

By 2030, I envision a Nigerian film ecosystem with three healthy tiers: large commercial productions for theatrical release, mid-budget films for streaming platforms, and a robust independent sector supported by grants, festivals, and specialized distribution. Each serves different functions; all contribute to a diverse industry.

Getting there requires several interconnected interventions. First, genuine economic growth and stability. This is both an economic imperative and a distribution framework issue. Nigerians simply need to earn more to meaningfully engage with Nigerian cinema and increase industry profits. Policy intervention must follow: tax incentives for film production, protection of intellectual property, and establishment of film education institutions. These aren't radical requests; they're standard practice in film industries globally. We need private investment-not just in production, but in exhibition infrastructure, post-production facilities, equipment rental houses, and training programs. This requires patient capital that understands that cultural ROI extends beyond immediate financial returns. Regional distribution networks are equally critical: pan-African platforms that allow Nigerian films to reach audiences in Ghana, Kenya, South Africa. The African diaspora represents 200+ million potential viewers largely underserved by current distribution.

Conclusion: The Long Work Ahead

I'm currently in post-production on a TV series while developing two more projects. Each project teaches me something new; about craft, about collaboration, about the specific challenges of making cinema in Nigeria. The work is harder than it should be, and slower. But it's happening.

When I started making films, I simply wanted to tell stories set in Ibadan - to show that meaningful cinema could emerge from anywhere in Nigeria, not just Lagos. A decade later, that vision feels like it seeded something larger. It proved that sustainable creative economies can exist outside traditional centers, that decent work in the arts is possible even in difficult environments, that we can build our own infrastructure when institutions fail to provide it.

This is the new Nigerian cinema: not waiting for perfect conditions, but creating the conditions we need. It's incremental, it's imperfect, but it's ours. And it's working.

Bibliography

Africa International Film Festival (AFRIFF). Official Website. Lagos: AFRIFF, 2024. Available at: https://afriff.com

Amazon Prime Video. Prime Video Nigeria. Amazon.com, Inc., 2025. Available at: https://www.primevideo.com

Netflix. Netflix Nigeria. Netflix, Inc., 2025. Available at: https://www.netflix.com/ng

Egunjobi, Taiwo, dir. In Ibadan. Sable Productions, 2019.

- All Na Vibes. Sable Productions, 2021.

- A Green Fever. Sable Productions, 2024.

- The Fire and the Moth. Sable Productions, 2025.

United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations, 2015. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. United Nations, 2015. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal8

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure. United Nations, 2015. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal9

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. United Nations, 2015. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11

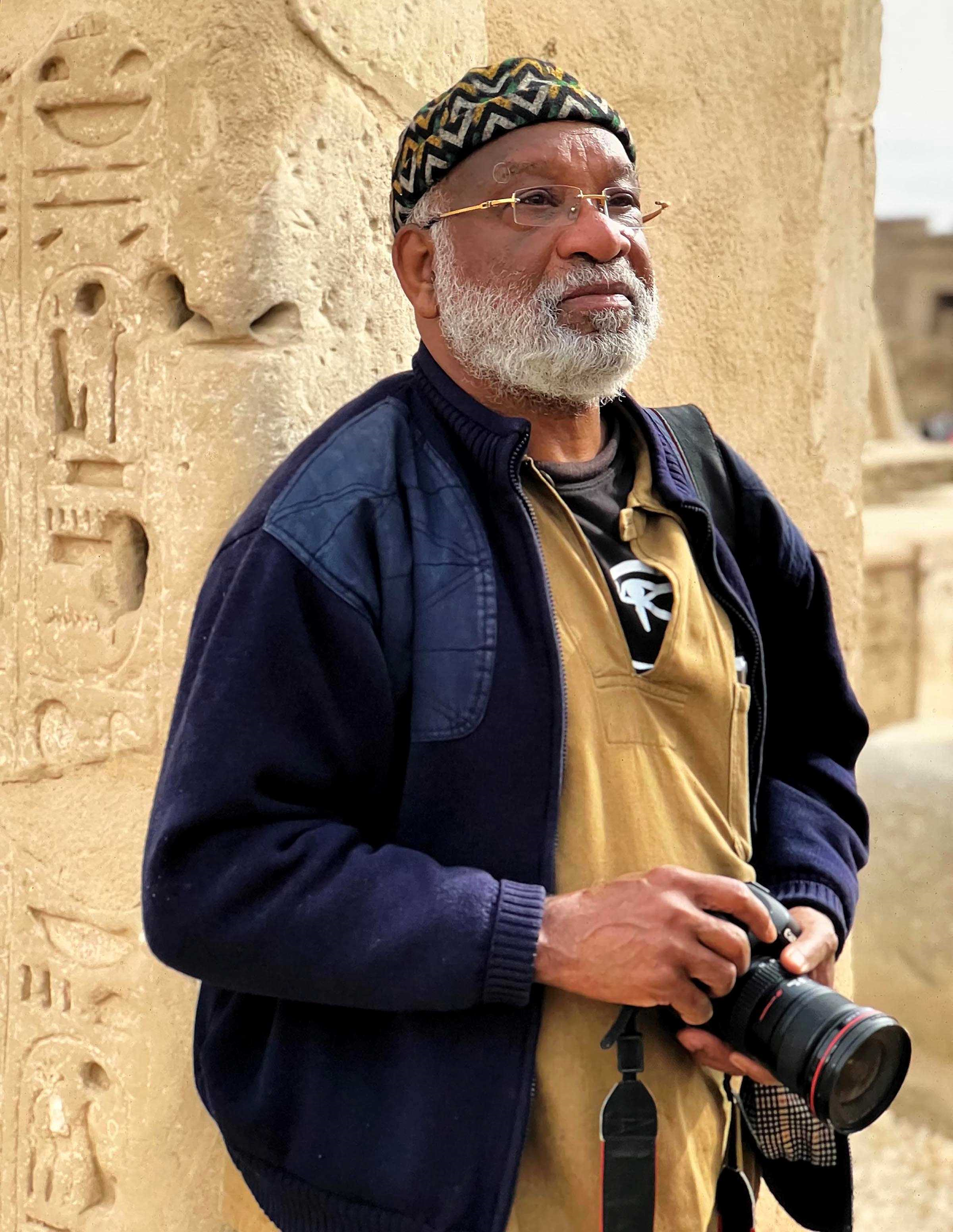

Taiwo Egunjobi- Career Profile

Taiwo Egunjobi is a Nigerian filmmaker. He holds a B.Sc. in Psychology from the University of Ibadan and began making films as an undergraduate.

His feature films - In Ibadan (2019), All Na Vibes (2021), A Green Fever (2024), and The Fire and the Moth (2025) have screened at international festivals including AFRIFF, Nollywood Week (Paris), and have been distributed on Kweli TV, Netflix, Amazon Prime Video. His work is characterized by genre storytelling and atmospheric tension.

Egunjobi co-founded Sable Productions, a production company focused on independent Nigerian cinema. He frequently collaborates with screenwriter, Isaac Ayodeji, and has become a prominent voice in conversations about sustainable models for independent African cinema.

His films have been praised for their visual language, social commentary, and contribution to expanding Nollywood's cinematic vocabulary beyond commercial conventions.

Author: Taiwo Egunjobi

About the African Perspectives Series

TheAfrican Perspective Series was launched at the 2022 Nigeria International Book Fair with the first set of commissioned papers written and presented by authors of the UN SDG Book Club African Chapter. The objective of African Perspectives is to have African authors contribute to the global conversation around development challenges afflicting the African continent and to publish these important papers on Borders Literature for all Nations, in the SDG Book Club Africa blog hosted in Stories at UN Namibia, on pan-African.net and other suitable platforms. In this way, our authors' ideas about the way forward for African development, can reach the widest possible interested audience. The African Perspectives Series is an initiative and property of Borders Literature for all Nations.

Copyright Statement

First published on Borders Literature for All Nations (www.bordersliteratureonline.net) as part of the African Perspectives Series.

Borders Literature for All Nations is registered with the Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC). Registration No. LW0620.

All rights reserved. Please credit the author and site when sharing excerpts.

For permissions, contact: info@bordersliteratureonline.net cc: bordersprimer@gmail.com

Updated and re-illustrated edition prepared for the anthology Living Sustainably Here: African Perspectives on the SDGs (2026).

© 2026, Selina Publications, (A division of Selina Ventures Limited)

Selina House, 4 Idowu Martins Street, Victoria Island, Lagos, Nigeria

Email: selinaventures2013@yahoo.com